Práticas tradicionais de caráter religioso

1.

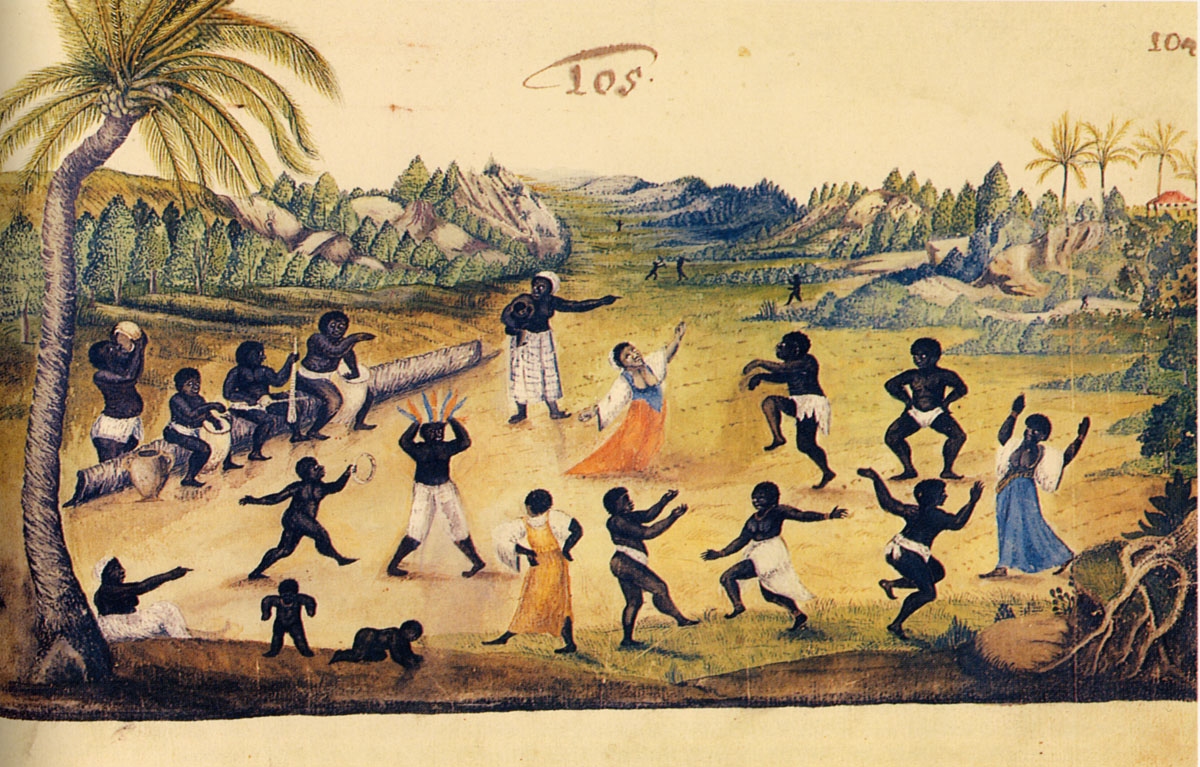

Cerimônia e dança no Brasil, ca. 1630.

Fonte: Cristina Ferrão &

José Paulo Monteiro Soares. (Editores). Brasil holandês (vol. II). O

"Thierbuch" e a "Autobiografia" de Zacharias Wagener. Rio

de Janeiro,

Editora Index, 1997, p. 193, prancha 105. Comentário: Homens,

mulheres

e crianças dançando. Grupo com vários instrumentos

musiciais,

incluindo tambores e outros instrumentos africanos. O

comentário do

próprio Wagener (p. 194) vale a pena ser transcrito: 'Quando os

escravos têm executado por semanas inteiras sua penosa tarefa,

lhes é

permitido festejar o domingo como desejam; estes, em grande

número, em

certos lugares e com toda sorte de curvos saltos, tambores e

pífaros,

dançam de manhã até a noite, todos de forma

desordenada entre si,

homens e mulheres, jovens e velhos; enquanto isso, os restantes bebem

uma bebida forte e preparada com açúcar, a que chamam

garapa; consomem

assim o dia santo santo em um perpétuo dançar, ao ponto

de muitas vezes

não se reconhecerem, tão surdos e imundos que ficam'.

2.

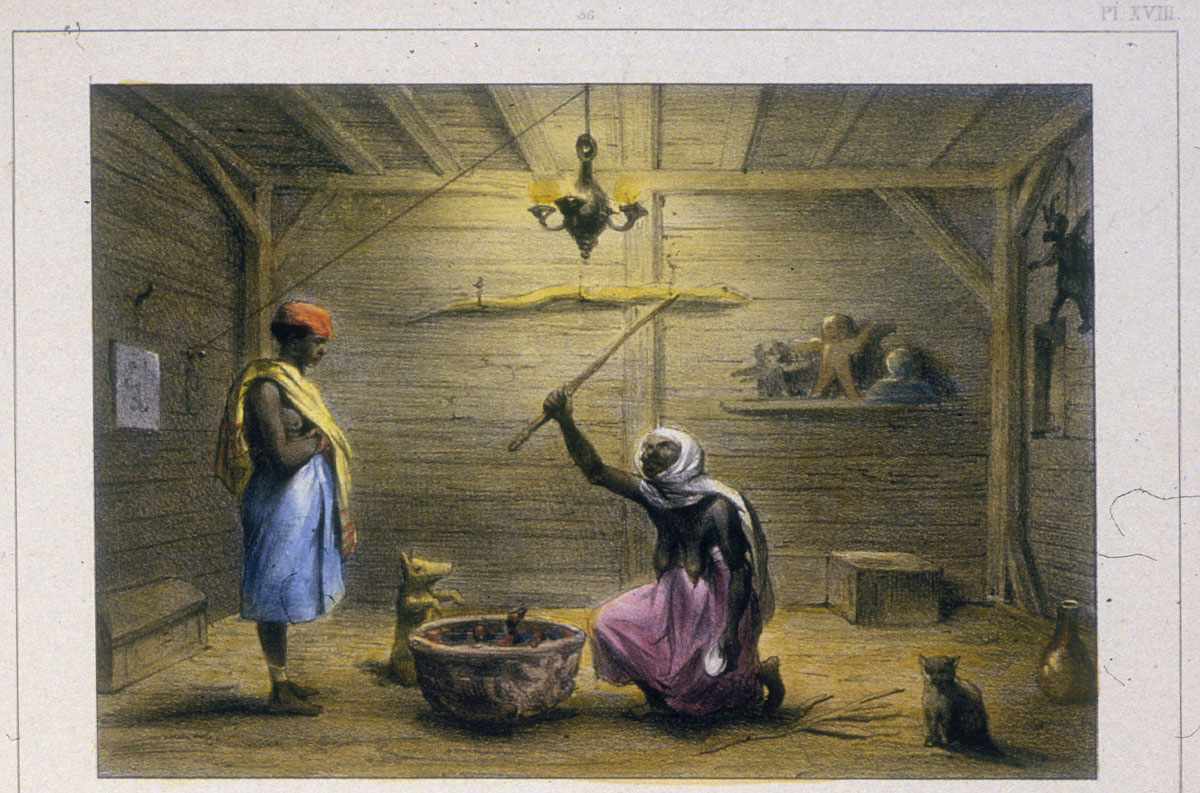

curandeira, Paramaribo, Surinam, 1839

Fonte: Pierre Jacques Benoit, Voyage a Surinam . . . cent dessins pris sur nature par l'auteur (Bruxelles, 1839), plate xvii, fig.36. Comentário: A healer trying to cure a client of some illness, using her spiritual powers. These healers, "who the Negroes view as oracles," are usually older black women and are called Mama Snekie (or Water Mama, Mama of Snakes). The author observed one of these women at work, and describes at length the scene he witnessed and illustrated in this drawing (p. 26).

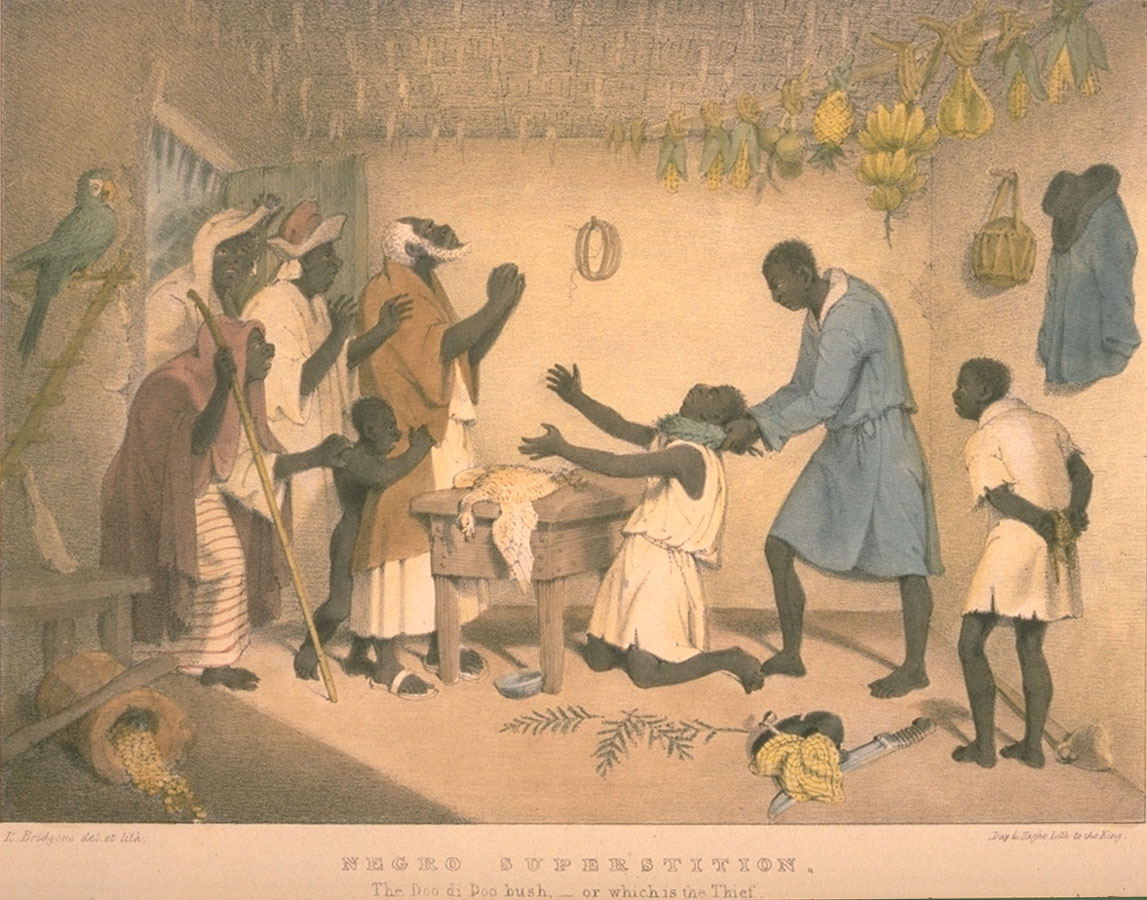

3.

Procedimentos para verificar um

ladrão, Trinidad, ca. 1830s

Fonte:

Richard Bridgens, West India Scenery...from sketches taken

during a voyage to, and residence of seven years in ... Trinidad

(London, 1836), plate 21. Comentário: Caption,

"Negro superstition, the Doo di Doo bush, or which is the thief." "This

is a kind of ordeal . . . among the Negroes, for extorting a confession

of guilt from persons suspected of theft or other crime .. . . The

ceremony is conducted with much solemnity. The injured party

communicates his suspicions to the Dadie (as the reputed sorcerer is

called), who appoints a time for the trial. A refusal of the suspected

person to accept the challenge is considered an admission of guilt. . .

. The Dadie twists a band out of the branches of a common shrub, at

intervals sprinkling salt on it, and accompanying the operation with

some incantation . . . . thus formed, it is passed round the neck of

the supposed culprit, who is then called upon to clear himself by oath

of the imputed crime. The Negroes . . .. believe that if they perjure

themselves .. . the band would remain immovably twisted round the neck,

and, by gradually tightening itself, ring from the party an

acknowledgment of his guilt . . . . the sketch here given was taken

from a scene which passed under the eye of the author" (Bridgens).4.

Feiticeiro Negro, Rio de Janeiro, ca.

1830.

Fonte: Jean Baptiste Debret.

'Feiticeiro Negro', aquarela pertecente a Fundação

Biblioteca Nacional (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil). In: Nelson Aguillar

(Org.). Mostra do

redescobrimento: negro de corpo e alma. São Paulo,

Fundação Bienal de São Paulo, 2000, p. 164.

Coméntario: A imagem de Debret (1768-1848) representa um homem

negro, bem vestido, e investido de poderes mágicos. No

chão, ele descreve um círculo, talvez representando uma

figura alegórica e ritual. Muitas

vezes, como se lê em alguns artigos e capítulos de livros

aqui

propostos para discussão (particularmente naqueles escritos por

João

José Reis) alguns desses homens poderiam, graças aos seus

poderes mágicos, gozar de posições importantes

decorrentes de suas relações com pessoas situadas dentre

os grupos de letrados ou de grandes proprietários da

América portuguesa e do Brasil imperial.

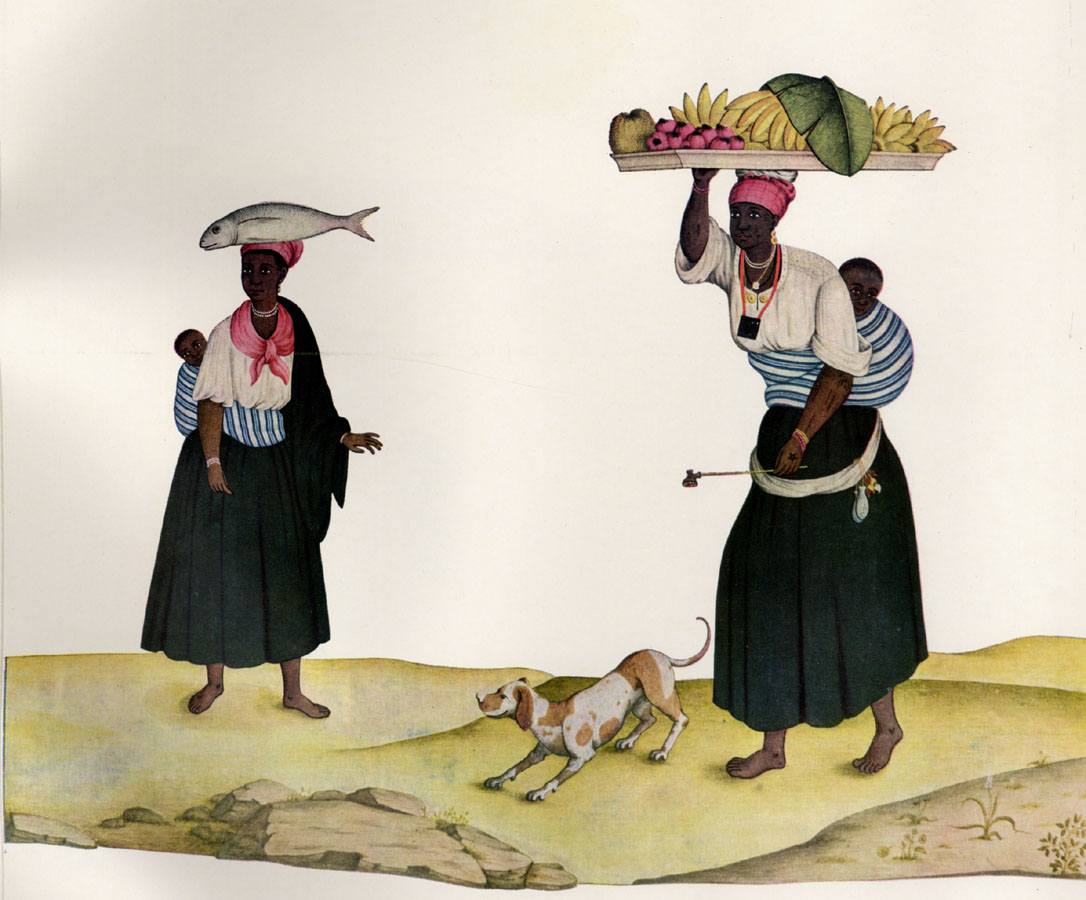

5.

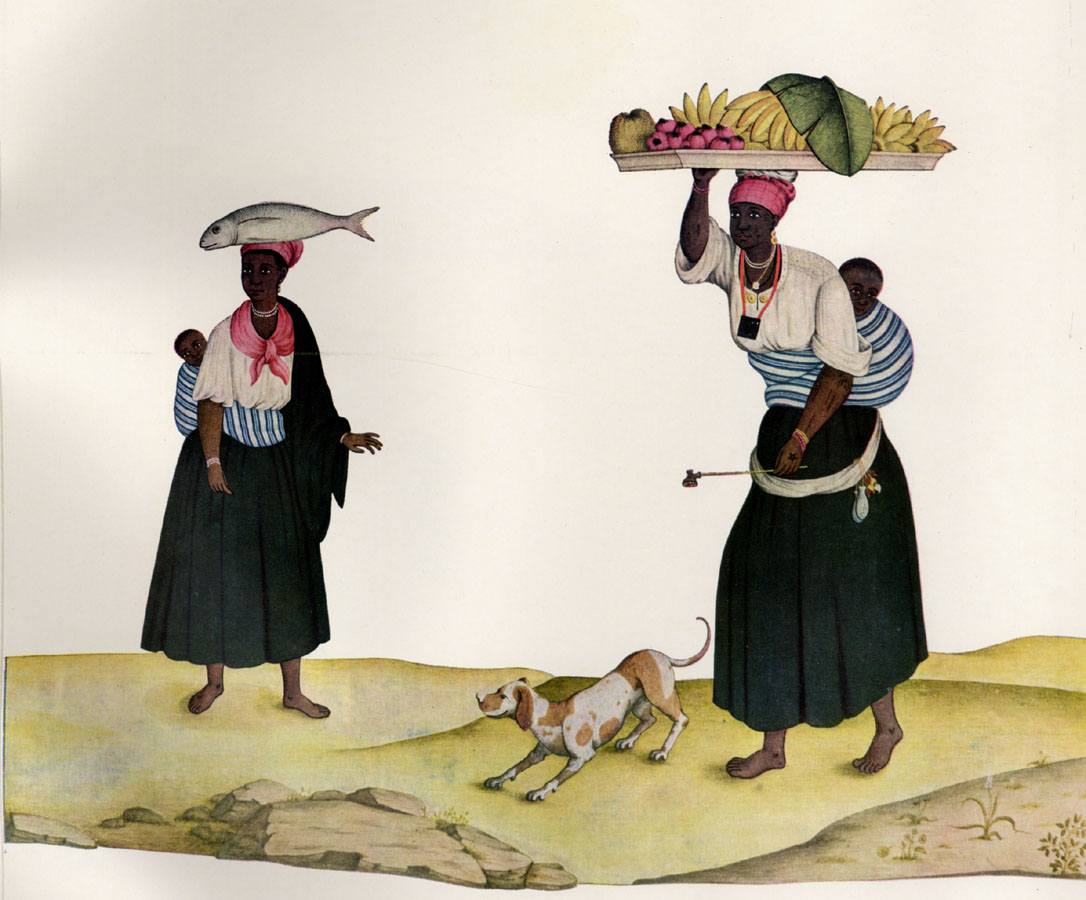

Vendedeiras com bolsa de mandinga, Rio de Janeiro, século XVIII.

5.

Vendedeiras com bolsa de mandinga, Rio de Janeiro, século XVIII.

Fonte: Carlos Juliao,

Riscos illuminados de figurinhos de broncos e negros dos uzos do Rio de

Janeiro e Serro do Frio (Rio de Janeiro, 1960), plate 33.

Comentário:

Showing

different clothing styles, the woman on the left carries a large fish

on her head, and her child strapped to her back. The woman on the right

is also shown with her child on her back, and is heading a wooden tray

filled with bananas and other fruit; note the long-stemmed pipe in her

hand and the amulets around her neck and hanging from the sash around

her waist. These amulets, or "bolsas de mandinga," were small pouches

"that contained powerful substances from the natural world--leaves,

hair, teeth, powders, and the like. Each bolsa had distinct powers, but

the most common ones were believed to protect the wearer from bodily

injury" (James Sweet, Recreating Africa: Culture, Kinship, and Religion

in the African Portuguese World, 1441-1770 [University of North

Carolina Press, 2003], p. 180). Born in Italy ca. 1740, Juliao joined

the Portuguese army and traveled widely in the Portuguese empire; by by

the 1760s or 1770s he was in Brazil, where he died in 1811 or 1814.